Ammon News - The Guardian - In the first months of 2014, in the midst of a crisis in Ukraine that recalls all but moribund European rivalries, much has rightfully been made of the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of the European civil war that would come to be known as the first world war. But, while the great war understandably looms large in western memory, it features prominently in the cultural memory of the west Asia–north Africa region too.

Here, we continue to live with the consequences of foreign intervention in the wake of the great war, of new borders drawn that failed to recognize the economic, social and environmental interdependence of the Arab lands in the Levant. The current polemics between the west and Russia – while Ukrainians and Syrians fight, suffer and die – are darkly reminiscent of the colonial mindset of a century ago.

The "great powers", after all, have a long tradition of ignoring nationalist aspirations that threaten their primacy. As the western press commemorates the first world war's centenary, it is also pertinent to recall that the Arab world is approaching its own anniversary – that of a new, pan-Arab national consciousness, built upon a celebration of centuries of Arab civilisation, language and culture.

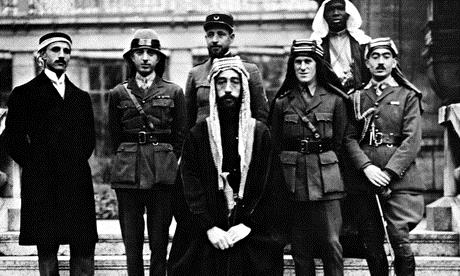

Born in the late 19th century, the Arab renaissance – out of which emerged the Arab Congress of 1913 – was a home-grown intellectual awakening calling for Arab unity and autonomy in the final days of the Ottoman empire. In 1918 our ancestors, encouraged by promises from the British Army officer TE Lawrence, hoped to realise their dream of an Arab nation without borders, founded upon the Wilsonian principle of self-determination and recognised by the international community.

Instead, our British and French "allies" doomed us to decades of divisive sectarianism and destructive rivalry, confined by borders that failed to match the economic, ethnic and environmental realities on the ground. The infamous Sykes-Picot agreement that partitioned west Asia into British- and French-mandated territories quashed the nascent Arab renaissance movement, forcing its sentiments to simmer under the surface of the Arab psyche and boil over only intermittently for the next century.

Today the Arab world continues to suffer from a lack of cohesion. We proudly state that Arabic is one of the six languages of the United Nations, yet as a region – indeed, as individual countries – we can agree on little else. This disunity is only fuelled by growing sectarianism in Syria, which – as noted in Margaret MacMillan's excellent book The War That Ended Peace – represents a worrying parallel with the Balkanisation that led up to the first world war.

Even my native Jordan, despite its long history of welcoming displaced fellow Arabs, is facing challenges to cultural unity. Jordan's population of about 6.5 million comprises not only native Jordanians, but hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, Iraqis, Egyptians and, now, Syrians. Sadly, rather than reject the arbitrary borders set by Sykes-Picot in favour of our shared Arab identity, political conversations here argue endlessly over who is "truly" Jordanian.

Our region's paralysing obsession with our differences, rather than our similarities, has led to damaging knowledge gaps in terms of accurate statistics on which to base policy. Fearful, perhaps, of what might be revealed, Lebanon has avoided holding a census since 1932, and Jordan since 2004. As a result we rely on often inaccurate, euphemistic or even irrelevant estimates, all of which avoid the crucial point: regardless of origin, many of the uprooted of the west Asia–north Africa region are fellow Arabs, each with a human need for food, water, shelter, dignity, freedom and a better life.

Accurate data is essential to determining regional carrying capacity, which will enable informed policymaking, allowing us to improve resilience and to respond collectively and more effectively to humanitarian emergencies such as the current displacement crisis – contributing to greater intra-regional trust and cohesion, rather than inciting discord. As David Owen stated in the Guardian last May, solving the Syrian crisis requires a regional settlement that is owned and developed by the region itself. This cannot be achieved without putting aside the rivalries caused by artificial, foreign-imposed borders.

As we approach the centenary of the Arab renaissance movement's message – driven and articulated by Arabs themselves – we should look back to its core principles of social cohesion and regional co-operation. We must recall that the concept of a pan-Arab identity was not born with the Arab spring of recent years, nor in Nasser's Egypt of the 1950s. Rather, it took root much earlier. At a time when Europe's own factionalism was tearing it apart, our ancestors in west Asia–north Africa were attempting to build a regional community of Arabs.

Only together can we solve the challenges facing our region. While the west commemorates the anniversary of what became the most destructive war human history had hitherto seen, we in west Asia–north Africa should honour the 100th anniversary of the Arab renaissance by attempting to rekindle its original principles of cohesion, dignity, and unity.

comment replay

comment replay