Ammon News - AMMONNEWS - Exiled leaders of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood are struggling to regroup, targeted by hostile Arab powers, cut off from senior colleagues imprisoned back home and challenged by angry young followers tempted to seek change by violence. Gathered over the past 10 months in Qatar, Turkey, Britain and elsewhere, hundreds of activists have isolated Egypt’s army-backed government diplomatically for last year’s removal of an elected Brotherhood-backed administration , Reuters reported.

The senior figures keep busy, shuttling between London, Doha and Istanbul to strategize in countries that still tolerate the movement, the standard-bearer of mainstream Sunni political Islam since it was founded in Egypt in 1928. But a political rebirth will be tough, even for a movement long adept at surviving repression and exile. Former army chief Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi, who deposed the Brotherhood’s elected president Mohamed Morsi last year and has since led a violent crackdown against its followers, is all but certain to win Egypt’s presidency in an election next week.

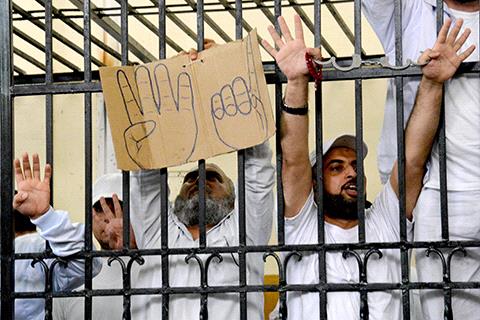

He says that when he takes charge, the Brotherhood, which seemed an unstoppable electoral force after autocrat Hosni Mubarak was toppled in 2011, will cease to exist. Hundreds of Brotherhood followers were gunned down on Cairo streets when the army destroyed a protest camp after Morsi was toppled last year. Thousands more have been rounded up and jailed. The 70-year-old leader of the Brotherhood, Mohamed Badie, and 682 supporters were sentenced to death on April 28.

Another revolution

That repression has galvanized the passion of exiles in those countries that tolerate them. Many shelter in Qatar, which funded Morsi’s government during his year in power and remains one of the only Arab states still friendly to the movement, despite pressure from its neighbors to withdraw backing. “There is no way in hell that I will vote for Sisi, the man who shed our blood and brought fear back into our country,” said Ahmed Rawag, 27, an Egyptian accountant in Doha who like many other expatriates boycotted overseas voting. “Mark my words: you will see another revolution against him soon.”

But despite such passion, sustaining the organization in exile, much less plotting a political comeback, may be difficult for a group that lost friends at home and abroad during Morsi’s year in office, when it was seen as trying to monopolize power. Nothing has come of tentative contacts via intermediaries to explore the idea of some kind of interim compromise with Cairo allowing Brotherhood activity, diplomats say. Brotherhood figures in exile say they are trying to learn the lessons of their failure to hold power. “Within Ihwan (the Brotherhood) there is deep self criticism and they have long meetings to discuss mistakes and what can be done in the future,” Ahmed Yusuf, a prominent, Turkey-based member of the youth section of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood.

“The Ihwan will learn a lot of lessons from this coup and will come out stronger.” Abdelrahman Ayyash, a former Egyptian Brotherhood member based in Turkey, said the movement – long used to dominating mainstream Islamist discourse – should now seek allies and form coalitions with others harmed by the military takeover. The Brotherhood “right now is still very arrogant … they need to open themselves up to some criticism”, he said. Others say the Brotherhood’s error was taking power too soon, before its cadres learned how to keep allies and govern.

“It was a mistake for them to enter something they were not ready for at all, and we are seeing the results today,” said Tarek Al-Zumor of the Building and Development Party, the political arm of the Gamaa Islamiya, a former hardline militant group that supported Morsi during his year in power. The Egyptian government blames the Brotherhood for Islamist unrest that killed hundreds of police and soldiers since Morsi’s fall.

The Brotherhood insists it opposes violence but says it is hard to get that message across when followers face such harsh repression and their democratic victory ended in disaster. “We are trying to reduce the fire of the youth and keep them with our stance, explaining to them any violence is damaging,” said Mohammed Ghanem, a Brotherhood leader in Britain. “The fact that there are some even considering violence, when we’ve been peaceful for our whole history, shows how intense the pressure is on them from the government.”

Refuges under fire

Those countries that have sheltered exiled Brotherhood leaders face pressure from Egypt’s military-led government and its backers – above all Saudi Arabia – to crack down. Saudi Arabia makes no secret of its hatred for the Brotherhood, whose strategy of promoting democracy to win power for Islamic governance challenges the principle of conservative dynastic rule dominant in the Gulf. Along with the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait, Riyadh sent billions of dollars in aid to Egypt after Sisi overthrew Morsi.

In April, Britain announced it was conducting a “review” – led by its ambassador to Saudi Arabia – to determine whether the Brotherhood posed any domestic or foreign security threat. The Brotherhood said it would cooperate, but UK-based Arab Islamists say the inquiry showed Britain had caved in to Saudi pressure, an assertion British officials deny. “Everyone knows (Prime Minister David) Cameron is trying to please the Saudis and UAE government. It is a gesture, and there is no evidence” of a Brotherhood threat, said Fareed Sabri, a London-based member of Iraq’s Brotherhood-allied Islamic Party.

The British capital is a centre for Middle East media, including Islamist publishers and broadcasters, and a haven for exiled Middle East opposition politicians. A diplomatic source said the United Arab Emirates disliked Britain’s recent granting of asylum to three Emirati Brotherhood sympathizers. Qatar’s tolerance for the Brotherhood has created a deep fissure among Gulf states. Diplomats in the region say Riyadh bluntly told Doha to stay out of Egypt’s election.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates also complain over Qatar’s granting of refuge to exiles after Morsi’s fall, including Brotherhood Secretary General Mahmoud Hussein. Qatar’s satellite broadcaster, Al Jazeera, continues to air sharp criticism of Egypt’s army-backed rule by figures like outspoken cleric Yusuf Qaradawi, based in Qatar, although his fiery commentaries have been less frequent of late. In a sign that Qatar is treading more carefully, a Western diplomat said the exiles were not given Qatari residency as in past decades, but merely permission for extended visits.