One of the bloodiest wars in European history was the thirty years war (1618-1648). Initially it began as a religious conflict between Catholic and Lutheran Christians. The disputed points concerned questions like how human beings can be justified before God, and the authority of the pope in the Church. Yet none of the issues dividing Protestants and Catholics were foundational: there was no disagreement on the nature of God, the role of Jesus Christ in salvation, or the text of the New Testament.

The state of hostility between Catholics and Lutherans lasted for another three hundred years. For all that time, each side tried to prove each other wrong. And at the end of the three hundred year period, there was about the same percentage of Catholics and Lutherans as there had been at the beginning. Neither side succeeded in converting the other.

But in the early twentieth century, small groups of Christians began a dialogue aimed at achieving mutual understanding. It did not aim at converting the other, but at understanding the other. Such a dialogue is difficult; it requires fair-mindedness, humility, a willingness to put aside stereotypes and to learn from the other, and patience. Instead of focusing on what was wrong with the other side, it proved more helpful to begin with focusing on what each side had in common-such as the common belief in God. This helped to build trust between parties. This in turn enabled the participants to discuss their real differences more amicably. And the differences turned out to be not as severe as each side had initially thought.

So, for example, the question of how one is justified before God was eventually resolved: the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America and the Roman Catholic Church were able agree on a Joint Declaration on Justification. More significantly, Catholics and Lutherans recently have been able to work together and live together in peace. Several of my colleagues at the University of St. Thomas (a Catholic University in St. Paul, Minnesota), are Lutherans. Differences still remain, of course, especially regarding the role of the pope, but the important point is that Catholics and Lutherans no longer fight each other, but can live, work, and marry together peacefully.

What might this mean for Muslims? I have been involved in Muslim-Christian dialogue for fifteen years. Sometimes at our dialogues both Sunnis and Shias are present. There is a lot of tension evident at these meetings, and it seems that Sunnis and Shias have not had much experience engaging in interfaith dialogue.

But what strikes me as an outsider is not how much difference there is between Sunnis and Shias, but how much each side has in common: they read the same Quran, acknowledge the same God and the prophethood of Muhammad, and hold most of the same doctrines and ethical values. I recognize that there are deep differences, but do not think these differences outweigh what Sunnis and Shias hold in common.

I believe that patient dialogue, aimed at understanding rather than at polemics and conversion would reveal this. So I believe that interfaith dialogue holds out some promise for Muslims. It will not resolve all differences, of course, but may at least lead to the ability of each side to live and work together peacefully, despite their differences.

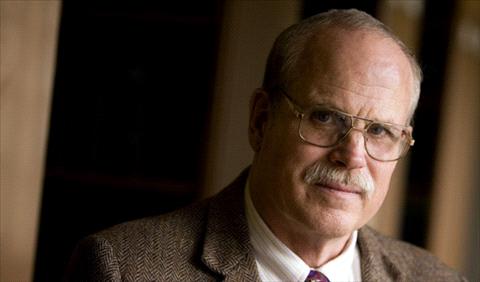

As Co-Director of the Center for Muslim-Christian Dialogue, at the University of St. Thomas, I believe that interreligious dialogue can lead to bonds of friendship between Christians and Muslims. We each worship the same God and hold many of the same values. As a Catholic Christian, I find much to admire in Islam, like the emphasis on prayer, fasting, and on God consciousness (takwa).

I am a better Christian as a result of my discussion with my Muslim brothers and sisters, many of whom are my friends. My dialogue with Muslims has not diminished my Christian faith, but rather enhanced it. Thus, it is my hope that interfaith dialogue both between Muslims themselves, but also between Muslims and Christians, can lead to a world in which we both can flourish and witness to God within our respective traditions.

Dr. Terence Nichols

Co-Director of the Center for Muslim-Christian Dialogue

University of St. Thomas

St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.A.