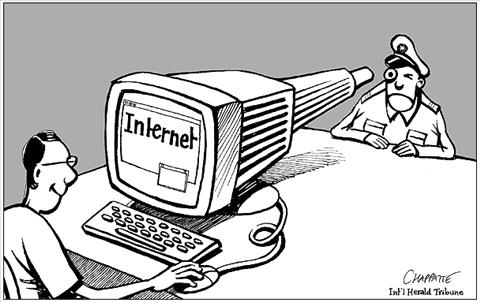

AMMAN — Jordanian journalists are up in arms after the government on August 3 passed a temporary law on cyber crimes seen by many as a way of controlling local news websites.

Late last month the government also barred civil servants while at work from accessing around 50 websites, mostly local news, in what it called an effort to improve productivity.

Journalists say the new law allows the authorities to raid and search offices from which websites are published and to access computers without prior approval from public prosecutors.

"The law was written in an elastic way so the government can interpret and implement it the way it wants and according to its interests," Mohammad Hawamdeh, managing editor of Khaberni (Tell me) online news agency, told AFP.

"For example, if I want to publish an article about any social, economic or political issue, under the new law I could be accused of harming Jordan's interests and economy."

Like most journalists, Hawamdeh believes the real intention is a local news sites crackdown.

"The fact that the Internet ban and the law came out almost at the same time is suspicious. Why did the ban focus mainly on local news sites? It's clear the government is targeting us and wants to shut us up," he said.

The government denies this.

"The law was issued to cope with information technology developments as well as related legal issues and cyber crimes. It does not criminalise people for expressing their opinions," Information Minister Ali Ayed told AFP.

He also defended the Internet ban for civil servants, saying "work hours should always be used for work."

"We respect professional websites. We are not targeting anybody, for example we blocked the Petra news agency's site, even though it's state-run. We did not block sites like Google and Yahoo!"

A government study has showed that public employees who surf the Internet for an hour a day cost the state 70 million dinars (100 million dollars) a year.

International and local rights organisations have criticised the new law.

The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) urged King Abdullah II to veto the law, saying it "provides authorities with sweeping powers to restrict the flow of information and limit public debate."

It said the law addresses electronic crimes but also includes "broadly written provisions that could hinder online expression and restrict the ability of journalists to report the news."

The law also bans "sending or posting data or information via the internet or any information system that involves defamation or contempt or slander," but the CPJ says it does not define such crimes.

Samir Hayari, co-publisher of the Ammon news agency, another local popular news website, said the new measures "feel like we are under martial law."

"The ban and the new law is a backward step," said Hayari. "Nobody should prevent us from doing our work."

Lawyer Saleh Armuti, a former Jordan Bar Association president, told AFP the law is "unconstitutional because it affects freedom of expression, and the constitution is very clear about preserving freedom of expression."

"Another dangerous thing is that the law is temporary, and the constitution says the government can issue provisional laws only on urgent matters in the absence of a parliament. What's the urgency now to issue the cyber crimes law?"

Several publishers of local news websites at a news conference accused Prime Minister Samir Rifai of being an "enemy of the press."

"In my opinion, the government did all that to weaken the news websites because they publish reports on key political, social and security issues which the government does not like," said Mohammad Momani, a political science professor at the state-run Yarmuk University.

"Preventing employees from surfing the web will not improve productivity, so it's better to give them access to the Internet and have educated employees," added Momani, who also writes for Al-Ghad independent Arabic daily.

Some government workers agree.

"Upgrading our work will not be achieved by controlling our minds and thoughts. Those who want to waste time can always find ways to waste it, with or without the Internet," one ministry official said on condition of anonymity.

"I don't understand how the government can issue such a law and come up with such a ban when some of its members are on Facebook and Twitter, and they brag about it."

By Ahmad Khatib (AFP)

* Cartoon by International Herald Tribune